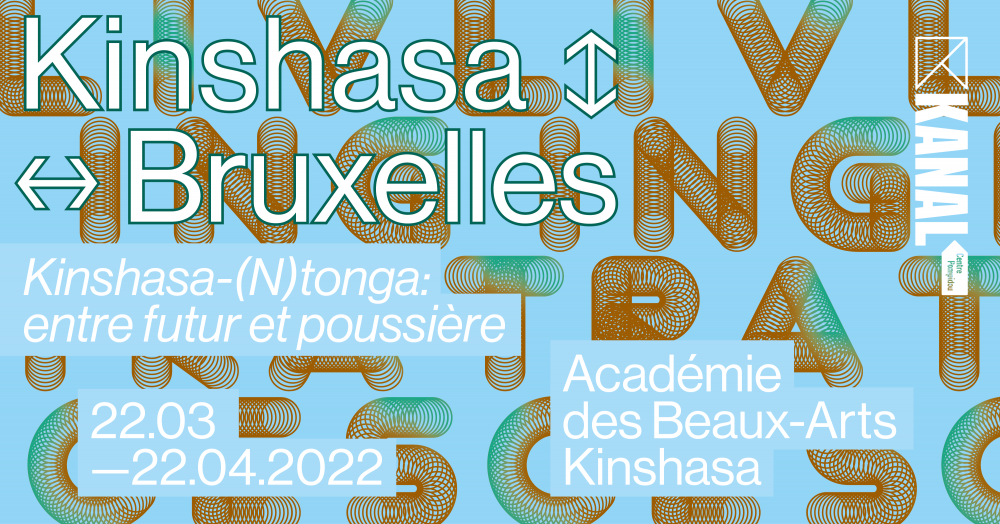

Kinshasa-(N)tonga

Entre futur et poussière

This project presents a confrontation between the rigid grid layout designed for the city and the human aspect and the fluid sensations therein; it is a combination of a multitude of fantasies around Kinshasa, a megalopolis of over ten million inhabitants. Kinshasa is a vast, sprawling city, often labelled as individualistic due to its SAPEUR (Dandy) character that has been built up in successive layers over several centuries. The narratives of ambition, nationalism, violence, technical innovation, and economic transformation, which are visible on the main avenues and in the parliamentary palaces, are intertwined with the narrative of spaces that have been cobbled together, of DIY and intimacy. The first traces of human settlement along the river date back to 500 AD but the development of the modern city did not get going until 1881. This global city, which enjoys the position of a world trade hub, was built anarchically despite ambitious urban plans for restructuring it. The city is marked by the results of this early town planning, which lasted long after independence, notably with the ‘bunkerisation’ of private housing. Modernist plans and unfinished buildings are scattered with everyday objects such as stools or gourds. These relics that testify to the survival of "rural" habits, recall the roots of Kinshasa like the baobab tree that marks the separating line of the Ngandu village where the tomb of Chief Mfumu Ngandu and the earthen house of his parents can still be seen. Contemporary art, design, and documents from archives complete this intimate view of the Congolese capital.

The aim of the exhibition therefore is to reveal the city via the many different ‘ways of doing and producing’ that have given the local residents the opportunity to transcend rigid definitions of its identity and function. Ntóngá - 'needle' or 'building site' in French - thus becomes a privileged term that, paradoxically, charts the way that building works destabilise the 'constructivist' architectural paradigm used to configure the entire scheme of representations of Western thought. As the artworks and objects in the exhibition reveal, long before Kinshasa became the playground of utopian fantasies - often followed by political nightmares – the city was a place of dreams and poetry.

Having inherited a secular tradition of crafts, the artists of Kinshasa artists also bring via their respective practices a powerful fantasy of this shared legacy of colonisation. Different aspects of this legacy are however challenged: Gosette Lubondo addresses these places of memory within the current social context, Azgard Itambo’s photographs reflect on colonial buildings and those built under Mobutu, and Magloire Mpaka Banona has created an archive made up of a collection of photographs of Kinshasa taken between 1900 and 1970, while Prisca Tankwey’s performance Léopoldville Mourning questions the colonial past, Sammy Baloji highlights DIY construction practices and utopias, and then there are the challenges posed by Filip de Boeck’s The Tower or Mega Mingiedi's futuristic drawings of the city, etc.

In dialogue with this artistic dynamism in Kinshasa, the audience will also be invited to reflect on the architectural work of Eugène Palumbo and Fernand Tala Ngai, who were very active during Mobutu’s campaign for a ‘return to authenticity’ during the 1970s. This doctrine aimed at erasing all traces of colonialism took the form of dismantling monuments and changing colonial names. Palumbo's work, which includes a large number of official and private projects, has remained in phase with modern architectural trends, whilst seeking to embody Mobutu's precepts of a hypothetically "authentic" culture.

Finally, the scenography, conceived in the form of Kinshasa-(N)tóngá, a city in the making - a city under construction, creates a space where the artists' works connect with archives and objects from another era.